From a concert of 22 harps played by young people between the ages of 7 and 17 in the Ulster Hall, Belfast on May 22nd, 1988, a phenomenon was born.

Janet Harbison came to Belfast in 1984 to research the music collected at the Belfast Harpers’ Assembly of 1792 for her PhD (Ethnomusicology), and in 1986, was appointed Curator of Music at the Ulster Folk Museum where the ‘traditional life’ and social history of Northern Ireland was preserved. This was a Department of Education managed facility and Janet was also involved in the development of the GCSE (Secondary School’s) curriculum which was being expanded to embrace local history and heritage, as was already represented in the curricula of Scotland and Wales. But, Northern Ireland was a colonised province by the British in the 17th century – and the legacy of this was a divided community with a British-dominated administration which lay at the root of the 20th century civil unrest called ‘The Troubles’. Violence had broken out after the Civil Rights marches 1968 and, for over 37 years, the daily experience of life in Northern Ireland was marked by riots, bombings, burnings, fear, death and destruction – grief and bitterness. With Janet’s background of having descended from an Ulster-Scots planter, but being raised as Irish and nationalist (and fluent in the Irish language), she found that her political ambiguity allowed her to move and work with relative ease between the communities...

At the Folk Museum, one of Janet’s responsibilities was to give ‘representation to the cultural traditions of music and dance in Ulster’ and she arranged an annual calendar of events – celebrating all the various musical, song, dance and band’s cultures of both communities – but the playing of the harp was conspicuously absent from the programme despite its illustrious history and symbolic importance in the province. South of the border in the Irish republic where the harp is the Irish national emblem, there was a very active tradition of harping, with professional opportunities for players at weddings, business events and in tourism. In the north of Ireland, the harp was also the emblem of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, emblazoned on the uniforms of all the police. It was also the emblem of a number of the British army battalions in the province, and it was the emblem signifying the Irish quarter of the United Kingdom in the British Royal Standard (flag). The harp was not played in the province because of its political ambiguity – to which community did the players belong? In Northern Ireland, your cultural interests expressed your political identity.

Janet was also involved in the development of the GCSE (secondary school) curriculum with the inclusion of local heritage elements in the coursework, bringing Northern Ireland into line with Scotland and Wales. The education policy was ‘Education for Mutual Understanding’ and projects that would integrate the two communities were being encouraged. Janet conceived a project where she would teach the harp to children from both communities in Northern Ireland bringing them together after 2-3 years preparation to perform their collective story on stage together. While one half of the community would celebrate their music, they would also learn about the other, and perhaps come to appreciate the common ground between them. The first performance of the ‘Irish Harp Concert’ was in the programme of Belfast’s ‘Linen Hall Library’ bicentenary festival – where the library commemorated their role in the organizing of the original 1792 Belfast Harpers’ Assembly. The concert took Belfast by storm! The first half of the concertfeatured a ‘recreation’ of the 1792 event with 10 young harp players impersonating one of the ten that performed in 1792 – and the second half was a group concert comprising 22 players between the ages of 7 and 20 performing music arranged from the published and unpublished volumes of Edward Bunting, the music transcriber at the 1792 event.

The impact of the concert was augmented by the BBC Radio recording that made 2 radio programmes from the live event featuring both halves of the concert. These were broadcast and repeated a number of times because of the positive public response. Suddenly, many families wanted to have their children play the harp, and a number of instrument makers turned their hands to making harps. Some harps made by the interned prisoners in the ‘H Blocks’ (Maidstone Prison) started arriving in Janet’s classes – made by the young player’s fathers or uncles – but all were welcomed to get the project off the ground. The ‘social project’ of the ‘Belfast Harp Orchestra’ was taking flight. Political sensitivities were always a concern but Janet’s dual background of an Irish Catholic upbringing and an Ulster-Scots (colonial) background (and a Presbyterian husband!) guaranteed that the orchestra platform was a ‘meeting place’ for both traditions.

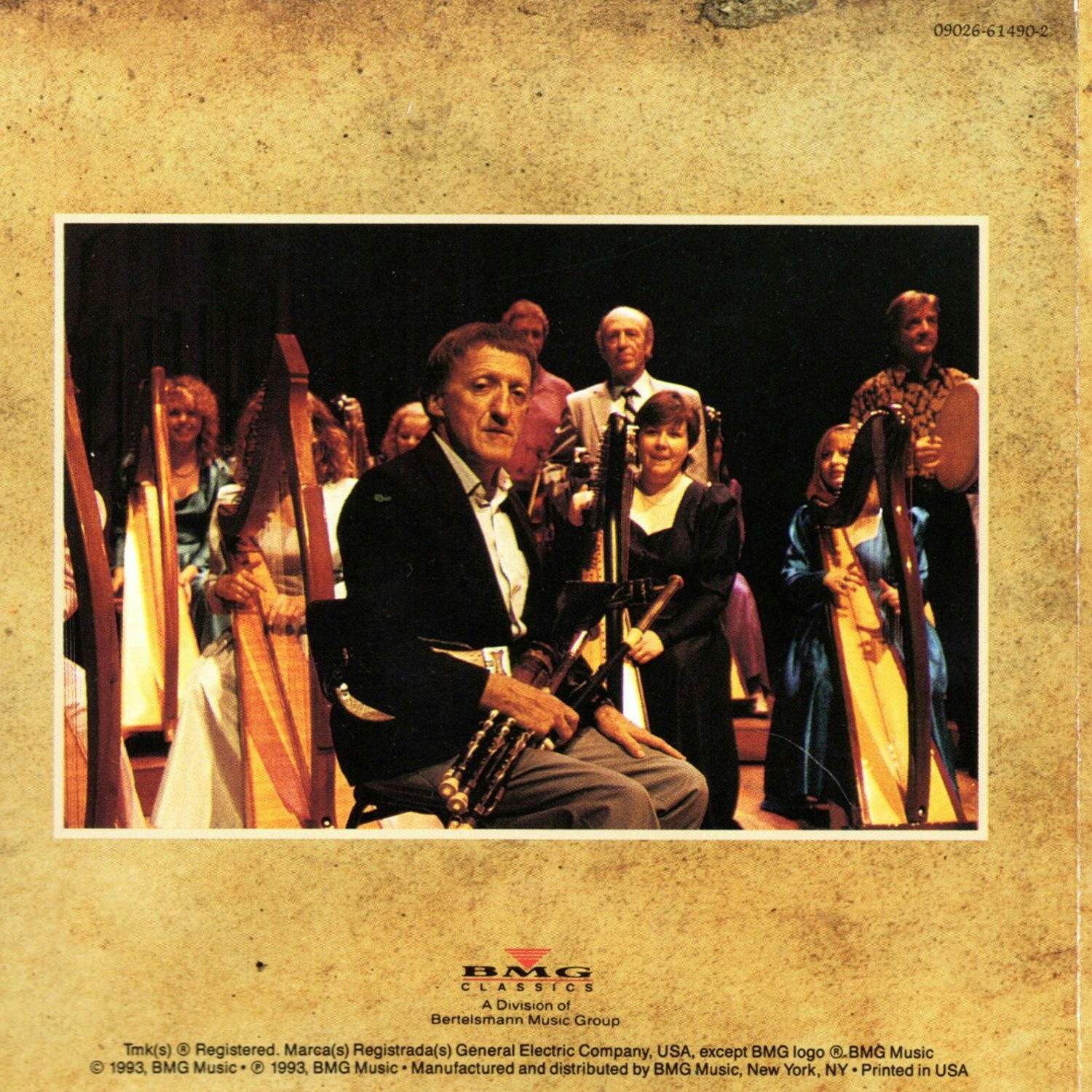

The Belfast Harp Orchestra was formally launched in 1992 celebrating the Bicentenary of the Belfast Harpers’ Assembly itself. After a first concert tour of all Ireland (20 dates in all the prime towns and a tour to Inis Oirr with an RTE television programme crew), the Belfast launch of the Orchestra was reserved for the opening concert of the World Harp Festival Belfast in May 1992 featuring the veteran group The Chieftains with the orchestra playing the first half of the concert. The Chieftains were so enamored of the Harp Orchestra that they were invited back on stage for a final encore set at the end of the concert and once again the public response was enormous. The Chieftains invited the orchestra to join them 2 weeks later for a concert at the National Concert Hall Dublin, where some tracks were recorded; and a week later at the Royal Festival Hall in London where some more tracks were recorded. The result was a collaborative album entitled ‘The Celtic Harp’ which won the top Grammy Award for a Folk Music Album in March 1993. Within one year, the Belfast Harp Orchestra was jettisoned into world focus – and a very different ‘good news’ story emanated from Northern Ireland. The potential for reconciliation was in focus and the orchestra played a significant part in driving it.

The Belfast Harpers’ Bicentenary festival achieved a phenomenal year of focus on the harp (which included a 6-month exhibition of artefacts from the Bunting Collection at the Folk Museum; a tour to ‘Irishfest’ at Milwaukee USA, the most prominent Irish festival there; a tour to Europe, a summer school, competition and a bicentennial recording project marking the state of Irish harping in 1992). Janet enjoyed significant support from various NI government agenciesincluding the Department of Education, Community Relations, Two Traditions and the Cultural Heritage departments and the orchestra was heralded by the media in many feature events.

After 1992, the orchestra training and operations became busy, Janet retired from her position at the Folk Museum and established the Harp Foundation (Ireland) to support the orchestra’s activities. The training centres and rehearsals were funded both through their concert earnings and their own professional harp agency ‘Belfast Harps’ and for 10 years, they thrived at home and abroad. The Belfast Harp Orchestra showcased Belfast (and Northern Ireland)’s history with the harp, spearheaded a divided community to a new understanding, spring-boarded the careers of solo harpers into many spheres of operation, and established bonds of friendship across the political divide. Numerous awards were bestowed in recognition of the orchestra’s role in in Northern Ireland’s ‘journey toward peace and reconciliation’ (including from the BBC, the Flax Trust and an honorary doctorate for Janet from Ulster University). The orchestra’s story was that of a community organisation that met the challenge of the shared identity of the potent symbol of state, that, inspired by the history, mystique and music of the harp, presented a unique opportunity to express their story together, in each of their musics, and in doing so, enraptured audiences in their story.

Through the years, many recordings were released, books were published, TV features and films were made featuring the Belfast Harp Orchestra (including ‘Harpestry’ by Polygram which became a ‘best seller’ in the USA) and concert tours were made through Europe, the Middle East and North America. Managed by the company Munchen Musik, the orchestra toured annually performing in most of Europe’s most prestigious concert halls and arts events, e.g. the opening of the Heineken Hall in Amsterdam, and regularly in the Philharmonic halls of Koln, Frankfurt and Munich. At home, they opened the Belfast Waterfront Hall and featured in the interval film for BBC’s Young Musician of the Year. Sadly, having enjoyed the ‘cease-fire’ from September 1994, the return to terrorist violence in early 1997 was devastating and the German agency managing the Orchestra asked that the Orchestra change its name so as to ‘lose’ the Northern Ireland story as Europe had tired of the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles’. In 1999, the Orchestra’s European tour was billed as the ‘Irish Harp Orchestra’ rather than the ‘Belfast Harp Orchestra’ – and after a fire-bombing incident later that year involving her neighbors in Holywood, east of Belfast, Janet had to leave Northern Ireland and moved south to Castleconnell, Co.Limerick establishing the Irish Harp Centre. This was to become a new home for the Irish Harp Orchestra, a base for the summer schools and (residential) Harp College (which trained harpers from their first lesson to professionality and apprenticeships), and a publishing company for Janet’s growing portfolio of books and arrangements. Nevertheless, behind her, Janet left hundreds of harp players, all thriving and contributing to their communities, featuring in their festivals and establishing their own harp schools. The Belfast Harp Orchestra itself graduated over 100 professional players who areamong Irelands most celebrated performers, composers and other harp orchestra directors today. This is all a testament to the legacy of Belfast and the Belfast Harp Orchestra experience.

In 2016, Janet returned to Northern Ireland as Visiting Professor of Music at Ulster University at Magee College, Derry (Londonderry), and the Irish Harp Centre was planned to open in September. But, just one week before Janet took up residence on July 1st, Brexit (UK’s vote to leave the EU) happened and the opening of the Harp Centre was ‘put on hold’ like so many other projects. Plans were hatched to re-establish the Belfast Harp Orchestra in April 2020 – but in February, the Covid pandemic brought ‘lock-down’s and many cultural projects also went ‘on hold’ – not to be revived again. Janet retired the orchestra in February 2023 unable to secure insurances against further epidemic outbreaks. But the renaissance of Irish harping nationwide was more than assured – thanks to the great adventure and legacy of the Belfast Harp Orchestra.

Be the first to know about new courses, updates on Harp weeks, upcoming events, concerts and more.

Copyright © 2026, Janet Harbison. All Rights Reserved

Site by Designmc